Dakota Reflections

Fossil Rim

Wildlife Center

Glen Rose Texas

Addax mom guarding newborn

I like Fossil Rim for several reasons: their conservation of endangered species, wonderful staff, public education, and from a photographer's perspective, the open pastures allowing photographs without fencing in the background.

Their mission- "Fossil Rim Wildlife Center is dedicated to the conservation of species in peril, conducting scientific research, training of professionals, responsible management of natural resources and public education. Through these activities, we provide a diversity of compelling learning experiences that inspire positive change in the way people think, feel and act towards nature."

The Fossil Rim Wildlife Center is one of the five founding organisation of the Conservation Centers for Species Survival (C2S2), a consortium created to develop programs for the sustanability of endangered species. The center brings the expertise of many large-scale zoological and environnemental institutions to adress issues related to the conservation of endangered species througt study, management and recovery plans. The central office of the consortium is in the Fossil Rim Wildlife Center.

Fossil Rim Wildlife Center participated in the reproduction and rehabilitation program of the Scimitar-horned Oryx in Chad and the rest of sub-saharan Africa. The species is extinct in the wild since the 1980's (poaching, loss of habitat and political strife are some of the causes of its decline), but a worldwide breeding program helped the restoration of the species. A first herd of 25 beasts was released in Chad in April 2016 with collars giving their position via satellite to follow them in their habitat. The Fossil Rim helped in the evaluation of the collar on their own herd inside the park to make sure the animals would not be incapacitated by them.

The center participates in a program to rehabilitate the Attwater’s prairie-chicken, a small groose native of the coastal plains of Louisiana and Texas, now one of the most endangered bird specie in America. Fossil Rim Wildlife Center and five other zoo initiated a breeding program for the specie in 1992. Between 170 and 175 birds are released in the wild every year, from which half of it were breed in the center. Even if the species has not grown in the wild, the project prevented complete extinction.

The center has one of the most successful cheetah breeding program in the world, with more than 175 feline bread and raise there

Addax

The addax is a critically endangered species of antelope. Although extremely rare in its native habitat due to unregulated hunting, it is quite common in captivity. The addax was once abundant in North Africa, native to Chad, Mauritania and Niger. It is extinct in Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Sudan and Western Sahara. It has been reintroduced in Morocco and Tunisia.

Blackbuck

The blackbuck, also known as the Indian antelope, is an antelope found in India, Nepal and Pakistan. The antelope is native to and found mainly in India, while it is extinct in Bangladesh. Formerly widespread, only small, scattered herds are seen today, largely confined to protected areas. During the 20th century, blackbuck numbers declined sharply due to excessive hunting, deforestation and habitat degradation. The antelope was introduced in Texas in the Edwards Plateau in 1932. By 1988, the population had increased and the antelope was the most populous exotic animal in Texas after the chital. As of early 2000s, the population in the United States has been estimated at 35,000.

Cheetah

Cheetahs are classified as vulnerable by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Cheetahs have suffered a substantial decline in its historic range due to rampant hunting in the 20th century. Several African countries have taken steps to improve the standards of cheetah conservation. By late 2016-early 2017, the cheetah's global population had fallen to approximately 7,100 individuals in the wild due to habitat loss, poaching, the illegal pet trade, and conflict with humans, with researchers suggesting that the animal be immediately reclassified as "Endangered" on the IUCN Red List

Dama Gazelle

The dama gazelle or addra gazelle is a species of gazelle. It lives in Africa in the Sahara desert and the Sahel. This critically endangered species has disappeared from most of its former range due to overhunting and habitat loss, and natural populations only remain in Chad, Mali, and Niger.

Fallow Deer

The name fallow is derived from the deer's pale brown color. This common species is native to western Eurasia, but has been introduced to Antigua & Barbuda, Argentina, South Africa, Fernando Pó, São Tomé, Madagascar, Mauritius, Mayotte, Réunion, Seychelles, Comoro Islands, Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Cyprus, Israel, Cape Verde, Lebanon, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, the United States, the Falkland Islands, and Peru.

Gemsbok

The gemsbok or gemsbuck is a large antelope in the Oryx genus. It is native to the arid regions of Southern Africa, such as the Kalahari Desert. Some authorities formerly included the East African oryx as a subspecies.

The gemsbok is depicted on the coat of arms of Namibia, where the current population of the species is estimated at 373,000 individuals.

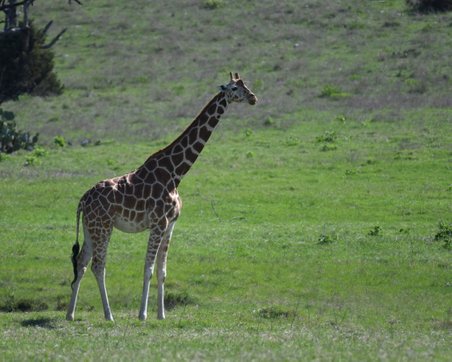

Giraffe

The giraffe is a genus of African even-toed ungulate mammals, the tallest living terrestrial animals and the largest ruminants. In 2010, giraffes were assessed as Least Concern from a conservation perspective by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), but the 2016 assessment categorized giraffes as Vulnerable. Giraffes have been extirpated from much of their historic range including Eritrea, Guinea, Mauritania and Senegal. They may also have disappeared from Angola, Mali, and Nigeria, but have been introduced to Rwanda and Swaziland.

Hartmann's Mountain Zebra

The Hartmann's mountain zebra (Equus zebra hartmannae) is a subspecies of the mountain zebra found in far south-western Angola and western Namibia. Hartmann's mountain zebras prefer to live in small groups of 7-12 individuals. They are agile climbers and are able to live in arid conditions and steep mountainous country. Their concervation status is classified as vulnerable.

Maned Wolf

The maned wolf (Chrysocyon brachyurus) is the largest canid of South America. Its markings resemble those of foxes, but it is not a fox, nor is it a wolf, as it is not closely related to other canids. It is the only species in the genus Chrysocyon (meaning "golden dog"). The maned wolf also is known for the distinctive odor of its territory markings, which has earned it the nickname "skunk wolf."

Mexican Gray Wolf

The Mexican wolf, also known as the lobo, is a subspecies of gray wolf once native to southeastern Arizona, southern New Mexico, western Texas and northern Mexico. It is the smallest of North America's gray wolves. Though once held in high regard in Pre-Columbian Mexico, it is the most endangered gray wolf in North America, having been extirpated in the wild during the mid-1900s through a combination of hunting, trapping, poisoning and digging pups from dens. After being listed under the Endangered Species Act in 1976, the United States and Mexico collaborated to capture all lobos remaining in the wild. This measure prevented the lobos' extinction. Five wild Mexican wolves (four males and one pregnant female) were captured alive in Mexico from 1977 to 1980 and used to start a captive breeding program. From this program, captive-bred Mexican wolves were released into recovery areas in Arizona and New Mexico beginning in 1998 in order to assist the animals' recolonization of their former historical range.

In 2017, there are 143 Mexican wolves living wild and 240 in captive breeding programs.

Roan Antelope

The roan antelope is a savanna antelope found in West, Central, East and Southern Africa. Roan antelope are one of the largest species of antelope. They are similar in appearance to sable antelope and can be confused where their ranges overlap. Sable antelope males are darker, being black rather than dark brown.

Sable Antelope

The sable antelope is an antelope which inhabits wooded savannah in East Africa south of Kenya, and in Southern Africa. When sable antelopes are threatened by predators, including lions, they confront them, using their scimitar-shaped horns.

Scimitar Horned-Oryx

The scimitar oryx or scimitar-horned oryx, also known as the Sahara oryx, is a species of Oryx once widespread across North Africa which went extinct in the wild in 2000. The scimitar oryx was once widespread across northern Africa. Its decline began as a result of climate change, and later it was hunted extensively for its horns. Today, it is bred in captivity in special reserves in Tunisia, Morocco and Senegal and on private exotic animal ranches in the Texas Hill Country. In 2016 a reintroduction program was launched and currently a small herd has been successfully reintroduced in Chad. In 2017, according to World Wide Fund for Nature the IUCN red list will downgrade the scimitar oryx from 'Extinct in the wild' to 'Critically endangered'.

Fossil Rim assisted in and participated with the reintroduction of the scimitar-horned oryx to Chad.

White Rhinoceros

The white rhinoceros or square-lipped rhinoceros is the largest extant species of rhinoceros. It has a wide mouth used for grazing and is the most social of all rhino species. The white rhinoceros consists of two subspecies: the southern white rhinoceros, with an estimated 19,682–21,077 wild-living animals in the year 2015, and the much rarer northern white rhinoceros. The northern subspecies had very few remaining, with only three confirmed individuals left in 2015.

Waterbuck

The waterbuck is a large antelope found widely in sub-Saharan Africa. Waterbuck are rather sedentary in nature. A gregarious animal, the waterbuck may form herds consisting of six to 30 individuals. These groups are either nursery herds with females and their offspring or bachelor herds. Males start showing territorial behaviour from the age of five years, but are most dominant from the age of six to nine. The waterbuck cannot tolerate dehydration in hot weather, and thus inhabits areas close to sources of water. Predominantly a grazer, the waterbuck is mostly found on grassland.

Wildebeest

The wildebeests, also called gnus, are a genus of antelopes, including two species, both native to Africa: the black wildebeest, or white-tailed gnu; and the blue wildebeest, or brindled gnu. Fossil records suggest these two species diverged about one million years ago, resulting in a northern and a southern species. The blue wildebeest remained in its original range and changed very little from the ancestral species, while the black wildebeest changed more in order to adapt to its open grassland habitat in the south.

History of Fossil Rim

In the early 1970s, Fort Worth businessman Tom Mantzel had a penchant for making money in the oil industry and a passion for exotic animals. In 1973, he purchased an exotic game ranch called “Waterfall Ranch.” He renamed the place “Fossil Rim Wildlife Ranch,” and enthusiastically set about adding to the exotic hoofstock herds that he found there. What began as a weekend retreat for Tom soon became a full-time obsession.

Growing concern over loss of wild habitat and species extinction compelled Tom to experiment in captive breeding at Fossil Rim. In 1982, he brought Grevy’s zebras to the ranch in his first effort to propagate an endangered species. Fossil Rim became the first ranch to participate in a Species Survival Plan (SSP) of the American Zoo and Aquarium Association (AZA). Success with the Grevy’s SSP spurred work with other endangered animals, such as the African addax.

By 1984, the near collapse of the petroleum industry was in full swing and hurting the Texas economy. To continue financing his species propagation programs, Tom decided to open the ranch to the public. With his small staff, he built a nine-mile road through 1,400 acres of hills, pastures and forests. Fossil Rim eventually opened a snack bar, a souvenir stand and introduced three new species – the Grant’s zebra, ostrich and reticulated giraffe.

Before long, Tom developed a volunteer program to help with the many school groups, scouts, organizations and individuals who wanted to see the unusual ranch with the extraordinary animals. While having fun and seeing new wildlife, people also were learning about the various animals, their habitats and the need to save endangered species.

Fossil Rim had developed a personality – a life of its own – as people were becoming aware of the facility and its mission. And though initially Tom hadn’t planned for his ranch to become a public attraction, he liked the interaction he saw between visitors and the animals.

Fossil Rim experienced great success with its early propagation programs. In 1985, the ranch acquired additional endangered species, including the African scimitar-horned oryx.

After lengthy communications with permitting offices, Tom also persuaded the U.S. government to allow him to import six cheetahs from South Africa. The cheetah program has grown into Fossil Rim’s greatest propagation success story with more than 175 cheetahs being born at Fossil Rim.

By 1987, Tom’s losses in the oil industry caused him to take a hard look at Fossil Rim. He realized the high maintenance costs of the ranch were draining him financially, but he refused to turn his back on the animals he loved. When he could no longer bear the costs of the ranch, Tom began a search for a partner.

Jim Jackson and Christine Jurzykowski were about to set sail on their own voyage of discovery. Both had worked hard to build successful, independent careers, and now they were ready for more.

While building their sailboat in Denmark, Jim and Christine happened to see a television program on the wildlife propagation efforts of John Aspinall, an English businessman turned conservationist. The story struck a chord in both Jim and Christine, who already were committed to conservation, but were looking for a hands-on way to take action.

The images of one man’s work to save endangered species were powerful and provocative. The fact that he was successfully breeding wild animals that might otherwise disappear forever drove home a crucial point – one person really can make a difference. Although Jim and Christine had long supported conservation efforts philosophically and financially, they had no actual experience with wildlife.

The idea that they could develop a wildlife preserve, much as Aspinall had done, and make a substantial contribution to conservation had enormous impact upon their lives. Without any background in wildlife science, other than personal interest, Jim and Christine had a lot to learn.

They researched the subject voraciously, planning to buy land on the Caribbean island of Martinique to develop as a wildlife preserve for land and marine animals. It was while seeking advice from animal propagation experts that they first learned of Fossil Rim.

When Tom Mantzel heard about their inquiries, he approached Jim and Christine about participating in Fossil Rim’s efforts. After discussing Tom’s goals for the ranch and his financial difficulties, they decided to help.

Initially, Jim and Christine advanced Tom operational funds for the ranch. Shortly thereafter, they learned that foreclosure was imminent. Realizing they had to make the ultimate commitment or witness the loss of Fossil Rim and its wildlife, Jim and Christine negotiated to buy the ranch. After a difficult transition that took them from partnership to outright ownership, the ranch became Fossil Rim Wildlife Center on May 7, 1987.

Reference:

http://fossilrim.org

Denise McDonough, Dr. Pat Condy, Stephen McDonough

Baby White Rhino

Fossil Rim, Texas

February 4, 2012

Building a world class conservation center is not easily done!

Africa to Antarctica to America: Condy’s journey by Tye Chandler

He has witnessed a lot of positive change over the years at Fossil Rim Wildlife Center, and now Executive Director Dr. Pat Condy has decided change is in order for him personally. After 14.5 years at the helm of Fossil Rim, Condy will be taking a sabbatical in October and return to the wildlife center in 2018 with a different role. Before focusing on the future, however, Condy shed some light on his Fossil Rim years, as well as his past.

Dr. Pat Condy served as Fossil Rim Executive Director from 2003 until 2017. He will return in 2018 in a part-time advisory and ambassadorial role. Born in Zimbabwe – known then as Rhodesia, Condy lived there until age 22. Earning his Bachelor of Agriculture in Animal Science degree in South Africa, Condy received a Rhodesian government bursary from the National Parks & Wildlife Department and returned home to work for that organization.

He would go on to earn a master’s degree jointly from the University of Oxford and the University of Rhodesia in Tropical Resource Ecology. Condy was one of four people chosen for the newly created Master’s Program supported by the National Parks & Wildlife Department, which was a 14-month course. At the encouragement of his professor in the program, an amazing opportunity arose the following year. “The Mammal Research Institute of the University of Pretoria in South Africa had just received a five-year contract to conduct mammal research in South Africa’s Antarctic Program,” Condy said. “My professor suggested I apply for that. I was a landlocked wildlife biologist who knew nothing about marine biology, but it intrigued me. Eventually, I applied, got a call to interview and got the job.” Later that year, he arrived on Marion Island, the largest of the Prince Edward Islands that were South African territory in the Sub-Antarctic Indian Ocean.

“We were there primarily to do seal research, and that eventually shifted to whale and penguin research, as well as the mice and cats that had been introduced to the island decades earlier,” he said. “The mice and cats were devastating the sea bird populations that used the islands as breeding platforms. The only mode of getting around that island was on foot, and it took about 5-7 days to traverse it depending on weather.” Condy lived on Marion Island and then mainland Antarctica for a total of two years and spent four summer seasons on expeditions to the Antarctic mainland researching seals, whales and penguins. He received his PhD through the Mammal Research Institute. Soon after, he was hired by the South African Council for Scientific and Industrial Research to expand the scope of research on Antarctica. “For a decade, I was scientific director for the South African Antarctic Program,” Condy said. “We had about 400 scientists from universities and government labs all over the country, involved across biological sciences, earth sciences, ocean sciences and atmospheric sciences programs.”

He still traveled frequently to Antarctica and Sub-Antarctic Islands to observe progress of the research. Meanwhile, he married his wife, Ymke, in 1982. They would have two boys – Richard and Christopher – and a girl, Jacqui. Years later, wanting to spend more time with his growing family, Condy ended his tenure with the Antarctic Program. “A friend of mind in Pretoria was building a lot of townhouses at that time, and he needed help,” Condy said of a new career path. “He needed someone in-house to source some of the needed materials, rather than buying from building suppliers. I did that for three years by skipping the middleman and purchasing directly from the manufacturers. “It was fun. It got me out of wildlife and science and into the business world. I learned a lot about cash flow and profit and loss.”

The animal world would come calling again, as Condy joined the Johannesburg City Council to become executive director of the Johannesburg Zoo. “It was an opportunity to get back into wildlife, plus my first exposure to the captive side,” he said. “I was tasked with reorganizing the zoo, building its tourism trade and its economy in order to eventually privatize it as a self-funding nonprofit entity. It’s 250 acres – a very big, pretty zoo. “That was my first exposure to the zoo world, as opposed to free-ranging wildlife. It allowed me to mix wildlife and business.”

After nearly a decade with the zoo, Condy resigned and moved to America. “First, I was the director at a small zoo in Florida as a transitional move of sorts,” he said. “Then, I moved north to work at Boston University’s offshoot called the ‘School for Field Studies’ as academic dean. It had research centers all over the world, and for a semester students would go as a study-abroad experience, undergo normal classes and participate in the center’s directed research program before returning to their original school with Boston University credits. “Each center had a director and two faculty members. My role was to make sure the teaching quality at those centers met BU standards. I did that for two years, and it meant a lot of travel.”

As was often the case with Condy tackling a new professional endeavor, his next move came from an unforeseen opportunity. “I got a call out of the blue from John Lukas, who used to be the director at White Oak (Conservation) and was on the Fossil Rim board of directors at the time,” Condy said. “He asked me if I’d like to come down to Texas. I told him I was about to go to the SFS centers in Kenya for four weeks, but to please call me back. I hadn’t been back but a day or two and he was on the line again.” Condy agreed to come down and check out the wildlife center in November 2002. He would spend three days at Fossil Rim, being interviewed by the staff, volunteers and former owner Krystyna Jurzykowski. “I liked what I saw, in terms of the Africa-like landscape, but after talking to the staff it was clear this place was in dire financial straits,” he said. “But eventually, on Christmas Eve 2002, I reached an agreement with the board to take the executive director position.”

Right after he arrived for good in February 2003, Condy attended his first Fossil Rim board meeting. “They told me that, in their minds, there were only two options – close Fossil Rim down or give it back to Ms. Jurzykowski – only three years after the park become a nonprofit entity,” he said. “I’d just moved here only to be told that. I asked them to give me a chance – give it a couple of months.” Condy figured the first thing he needed to do was hunker down and make a thorough assessment of the finances to understand exactly what the wildlife center was up against. “My second week here, (then-Chief Financial Officer) Pam (Adams) walked into my office, pale as a sheet, and I knew something was wrong,” he said. “She said ‘We’ve got a problem. We can’t pay salaries; we have no money.’”

Condy later identified that moment as the low point in his quest to see Fossil Rim thrive. While there were more than 100 employees at that time, he would reduce that figure down to about 60 over the next two years. “We needed $175,000 to get us through the next two payrolls, plus pay the electric bill and a few other things,” he said regarding the aftermath of Adams’ revelation. “We already had $500,000 in loans needing to be paid back. I talked to our board chairman, who ended up getting that $175,000 from Krystyna – half as a gift and half as a loan.”

While her assistance kept Fossil Rim going at that point, Condy said he did have to cut salaries significantly in late 2003 and make another notable reduction a year later. “Tourism was nowhere near where it needed to be, and the marketing department among others during my early years here didn’t embrace tourism as the only way Fossil Rim could survive financially,” Condy said. “We had a $500,000 line of credit and we were using it up every slow winter season. We got down to $5 in that account at one point; it was touch-and-go. Those were tough times.”

Fortunately, he said 2005 went a bit better financially with another incremental bump in 2006. “We began to build the tourism trade; it was the only way to reach a self-sustaining future,” Condy said. “Not just through the admission fees, but the gift store, too. When I got here, it was only open on weekends, but we got it open daily during Spring Break 2003 to help pay for the $280,000 in merchandise on its shelves that vendors had not been paid for. At that time, the Overlook Café, The Lodge and Foothills Safari Camp were also only open on weekends.

“Bit by bit, we got these facilities open (daily) to bring in more money. Later, we started doing guided tours as a new source of revenue. We began to push Wolf Ridge education more, too.”

According to Condy, a crucial moment for Fossil Rim’s sustainability occurred in 2008. “Until then, Fossil Rim as a nonprofit was operating on leased property,” Condy said. “What if the landowner decides to kick you off? Plus, it wasn’t yet self-sufficient financially. Put those two together and it was very difficult to persuade donors to get involved (when we cannot promise the future). “The board had been quite successful in persuading various individuals to make loans to Fossil Rim, so those also had to be paid off. Eventually, most of them very kindly and graciously gifted their loans. “When Krystyna donated the land in 2008, that was probably the biggest development of all in my time here. Then, Fossil Rim became landowner and operator. Now, it is also financially self-sufficient, so it is much more attractive from a donor point-of-view.”

Beyond the finances, Fossil Rim has changed in many other ways over Condy’s 14-plus years. “The new roads, new Nature Store, new parking lot at the Overlook, plus Wolf Ridge (Nature Camp) has been upgraded a lot,” he said. “We have a lot more tour vans now. I remember the first one. The Lodge and (Foothills) Safari Camp have been revamped considerably. “Support Services (department) has a lot more equipment now. At one point, it seemed like everything was fixed with baling wire.”

Two plots of land have been purchased during Condy’s tenure – covering 200 acres – near The Lodge and the Jim Jackson Intensive Management Area. “The animal population dropped to about half of what it is now, because they were being sold essentially to keep the lights on before and during my first couple of years,” Condy said. “During my time here, we have added Hartmann’s mountain zebras, aoudad, dama gazelle, black-footed cats, mountain bongo, Przewalski’s horses, roan and possibly a few others.”

The general improvement of Fossil Rim’s situation in recent years definitely helped Condy make his latest decision. “Now, Fossil Rim has a healthy economy, it is back over 100 employees and tourism has expanded enormously thanks to our marketing department,” he said. “And through its species conservation work, it has a national and international image and reputation out there in the big, wide world. There comes a time in life when it’s time to consider your situation. I am in my 70th year now, had a full and interesting life across three continents, an outstanding wife for more than half of it and three fine children and their families, so I’m happy to be taking a break from October until January before returning in an advisory, ambassadorial, part-time role.”

COO Kelley Snodgrass will be stepping in as interim executive director. Snodgrass has worked at Fossil Rim since it opened in 1984. “I feel good about Kelley stepping in,” Condy said. “He’ll be good. He’s worked here since college, so he knows just about everything there is to know about Fossil Rim and has been through its ups and downs since Tom Mantzel started the place.” On that note, Condy expanded on the many staff members he has worked with over the years. “It’s a wonderful staff,” he said. “I’ve always been impressed by their deep commitment and dedication in all departments. This kind of operation in the countryside – people who work in this rural setting do it for a cause – conservation of selected species and outdoor education of children, which are two crucial pursuits for a future in which the natural world will hopefully be considered very precious. “They aren’t just here for a job. That approach promotes dedication, and you see that in the staff across all the different activities here; it’s a great thing.”

Regarding a facility centered on conservation, it is appropriate that “protect” was on Condy’s mind. “Protect the cause,” he said. “Protect the spirit of Fossil Rim. That’s what people are here for, such as (longtime Animal Care staffers) Kelley, Arnulfo (Muro), Adam (Eyres), Janet (Johnson) and Mary Jo (Stearns). Turnover at the senior level is very low here, and it says something – people are working for the mission. “I enjoyed and was privileged to have a staff of different generations and both genders; we are about 60-percent female. The staff members here have so many different skills; it’s invigorating to witness.”

As it turns out, the range of topics covering all things Fossil Rim has brought great enjoyment to Condy during his tenure. “Fossil Rim is much more diverse than it would appear from the outside – so many departments come together,” he said. “That’s part of why I’ve enjoyed this so much. I get information on Nature Store sales, and then an hour later I’m talking with someone about a species conservation matter. “The next hour it could be visiting with a potential donor, then it’s about finances, and maybe later that day it’s about a marketing campaign. The variety has been nice.”

It has certainly been a roller coaster ride for Condy in his time at Fossil Rim, but not unlike his years in Antarctica, he stayed determined and focused on the task at hand to see the facility through its darkest hours. Protect the cause, the spirit and the mission. He practiced what he preached.

Reference:

http://fossilrim.org/2017/09/22/africa-to-antarctica-to-america-condys-journey/